Sri Lanka is on the verge of becoming a poster child of IMF reforms. The country’s inflation has dipped to a single digit after two years, being one of the highest in the world a year ago (Ondaatje 2023). At a time when many Asian, African, and Latin American (peripheral market) countries are facing severe economic and balance of payment stress and likely to seek IMF bailouts sooner or later, such narratives of success or failure are important to these countries (Reuters 2023). They are also important to international financial institutions (IFIs) such as the IMF, who are champions of eliminating price controls, deregulating capital flows, and dismantling trade barriers, what is often called the ‘neo-liberal agenda’.

At a different level of the same play, the local implementation of these IFIs-led reforms by groups of local elites with access to state power do not always align with the intentions of a global agenda of neoliberalism. IFIs are not always well-intended players whose intentions get hijacked by local elite power plays; rather they remain active enablers of state coercive power and passive commentators of its abuse.

Local elites that implement these reforms try to consolidate their power by elbowing out other elite groups and gatekeeping new competitors. In implementing reforms, these elites externalise the costs of debt and reforms to a wider and less-powerful section of the society. The post-Covid economic stress that led to the debt crisis and mass protests have led to a policy window which those in power use to push through reforms in a heightened frenzy. How elite contestations play out define the way in which reforms are going to benefit a larger section of the society, or be democratised.

Elite politics involve a degree of competition, which is how elites try to elbow out their competitors or ring fence themselves with privileges. However, there are also moments when elites reach a consensus or ‘elite bargains’, when they see it is in their self-interest to come to a working agreement, when they realise either, they cannot benefit further, without opening up for further competition and innovation, or when they realise that without a bargain, it is impossible to prevent a future elite from challenging the prevailing order (Nye 2011). The perceptions of the elites may sometimes be based on false reading of the situation too. However, the most significant failure probably arises from an elite group’s inability to preserve its long-term “class” interests. Elites find themselves legitimised as long as the system maintained by them creates a specific ‘public good’ (North, Wallis, and Weingast 2009).

Mapping elite groups against reforms

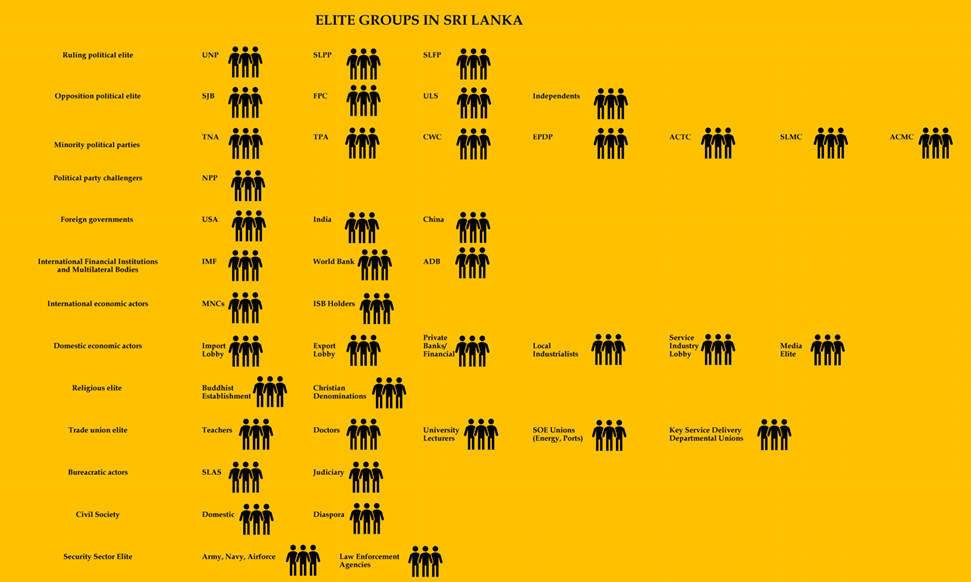

In this article, we identify key elite groups which have strong relevance to the ongoing reforms process. There are four categories of actors we look at. There is a significant overlap between these groups, and they respond to reforms in different and complex ways. While there can be long-lasting alignments among some groups of elites, others intra- and inter- elite group alliances are formed based on issues.

The first and possibly the most powerful group is the political elites in power, the opposition (often considered the government-in-waiting), and those who challenge the above two alternating elite blocs. These elites organise the people through political parties, using a combination of ideological narratives and patron-client relations (by way of various welfare schemes and privileges).

A second group of elites is foreign governments, international financial institutions, and multilateral agencies. These geopolitical actors influence national policies to derive desired outcomes in accordance with their geopolitical, commercial, and ideological interests.

Another group of actors is interest groups such as the civil society, trade unions, chambers of commerce or industries, etc. These groups generally maintain demands for fair play, welfare, and/or competition.

The rent-seeking clients of the regime is another small and powerful group. They come from among the businesses and relatively lower rungs of the political class. This group’s activities are based on strong patron-client relationships, and often involve interpersonal transactions of corruption and scandals.

Image 1: “Elite Groups in Sri Lanka,” Authors (2023)

Mapping key reforms across elite contestations

The reforms that are being deliberated since July 2022 and examined in this article are mainly constitutional amendments, bills presented in Parliament, proposed reforms (by way of concept notes or framework documents, or policy statements), or other structural reforms implemented by the executive. These reforms in turn can be broadly categorised into two types: governance reforms and economic reforms. The reforms below are selected to illustrate the contestations over the reforms process among elite groups.

| Governance Reforms | Economic Reforms |

| Anti-Corruption Bill | Domestic Debt Restructuring (DDR) |

| Anti-Terrorism Act | Labour law reforms |

| Amending the 20th Amendment to the Constitution | Tax reforms |

| Reforms regarding the 13th Amendment to the Constitution | SOE reforms; specifically restructuring loss-making public enterprises |

| Bills presented in parliament concerning electoral reforms | Legal reforms to enhance the independence of the Central Bank |

| Broadcasting Regulatory Commission Act | Aswesuma social welfare scheme |

| Online Safety Bill | Land reforms |

| NGO Secretariat Bill |

Table 1: “Type of Key Reforms in Sri Lanka, 2022-2023,” Authors (2023)

In the interests of brevity, we select four reforms which provide insights into how elite groups react to particular types of reforms.

1. Domestic Debt Restructuring

The government announced the restructuring of its domestic debt (DDR) at the end of June 2023. The proposed DDR is important to ensure overall debt sustainability, an essential IMF-bailout package pre-condition, and major international hedge funds that hold Sri Lanka’s bonds announced domestic debt restructuring as a prerequisite for negotiating restructuring their debt (Do Rosario and Campos (2023). The proposed domestic restructuring framework, which was passed in parliament with a majority vote covers around 40% of total domestic debt (Counterpoint 2023; Athukorala 2023). However, both short-term as well as long-term debt (in the form of treasury bills and treasury bonds), held by commercial banks has been exempted from the domestic debt restructuring.

This is a partial coverage of the domestic debt. Moreover, exempting banks from their long-term debt (bonds) is not usual in standard debt restructuring practice. Its implications are that the burden is transferred unequally to the pension fund contributors. This is partly a result of both the EPF (state-managed pension funds) and Central Bank of Sri Lanka (CBSL) being governed by the monetary board of Sri Lanka, which is not fully insulated from political pressure or insider dealing (NewsFirst 2020).

For the ruling elites, passing the burden on the least strong of the competing elites (i.e., the divided trade unions) appears to be the easiest way to restructure the debt. The terms of the DDR have exempted the banks, and this satisfies a small yet powerful group of local business elite, in whose hands ownership of private commercial banks and financial institutions is concentrating, and who have close links of patronage with the political elite (The Island 2023).

Unionisation among EPF-contributing workers remains strong in sectors such as the Free Trade Zones, banking, and some big SOEs (Telecom, Electricity Board, Petroleum, etc.). In the service industry, however, workers are generally poorly unionised. In each sector, some unions remain politically independent although major political parties maintain affiliated trade unions. At present, unions are highly divided and that makes them a relatively weak elite group.

For example, attempts to unite trade unions to negotiate more favourable terms for their pension funds, faced the challenge of JVP-led unions not committing to a common platform. The JVP, which forms the main political party in the NPP, poses a credible challenge to the establishment parties. Its interests are aligned more with using the present calamities to attract more voters than choosing a politics of solidarity. This factionalism among the lower rungs of the elite benefits the more powerful groups.

2. Labour law reforms

In May 2023, the government released a ‘concept note’ to replace 13 laws that govern the labour sector with what is commonly referred to as ‘the single law’. The proposal was presented to the National Labour Advisory Council and called for inputs from interested parties (Ministry of Labour and Foreign Employment 2023). While these reforms have some progressive elements such as increasing protections against workplace discrimination, bringing more female labour into the economy, and digitalising labour processes, they also have provisions that decrease accountability of employers to employees and weaken compensation mechanisms.

For the ruling political elite, reforming ‘outdated’ labour laws is aimed at reducing unemployment while promoting economic growth. This means encouraging foreign investment, through easy access to cheap and mobile labour. While the cabinet has not yet approved these proposed reforms, no major dissent has manifested from either the government or the major opposition parties. The JVP (main party within the NPP), which commands considerable trade union power, however, seems less committed to mobilising its full force against the reforms, compared to previous practice.

For domestic and foreign economic elites, this is a typical liberalising reform that secures individualist rights but stifles collective bargaining, and opens more space to exploit labour for potential increases in productivity and ease of ‘doing business’. The complementing interests among elite groups explain why these reforms never became a major topic of public debate beyond trade union and civil society circles.

Almost all major trade unions and union federations agree that the reforms have a negative impact on their members’ welfare. Large and small trade unions and several labour federations have jointly opposed the draft labour reforms claiming that they failed short of ILO Conventions governing tripartite consultation and failing to realise norms such as “decent work” (Dias 2023). Lack of due process and unfair gatekeeping tactics by officials have aggravated relations between the elite who implement reforms (political aides and civil service groups) and the trade unions. In one instance, before the introduction of the reforms concept note to the National Labour Advisory Council, the Commercial and Industrial Workers Union (CIWU) which had been a member since its inception was removed. This set a bad precedent as CIWU’s representative was the only female presence in the tripartite national advisory council.

The proposed labour reforms are illustrative of many of the problems in the way in which reforms are being introduced. These include the new “Employment Act” not being available in Tamil (violating the country’s official language policy), the lack of due process as these reforms come without a decision by the Cabinet, and a very short window for public consultation.

3. Anti-Corruption Bill

In April 2023, the Sri Lankan parliament passed an Anti-Corruption Bill without a vote. This bill replaces the previous laws on bribery, asset declaration, and the law that governed the Commission to Investigate Allegations of Bribery and Corruption (CIABOC). This reform claims to strengthen the CIABOC and comes at a time when the IMF announced it was conducting an “in-depth governance diagnostic exercise” (IMF 2023). The new bill has some progressive elements such as digitisation of declaration of assets, widening the types of professionals who had to declare assets, and strengthening the CIABOC’s capacity to collaborate with local and international law enforcement agencies to conduct investigations.

The fact that parliament passed this law without a vote means that there was considerable consensus among the political elite (ruling and opposition) on the new act. Opposition parties, such as the SJB, were keen to have provisions for asset recovery in the act (EconomyNext 2023). The NPP, the challenger to the establishment parties, also emphasised the need to have retroactive provisions, quoting large-scale corruption scandals during past governments. Key relevant civil society groups mostly welcomed the reform and adopted a correctionist approach, suggesting increased protections for whistleblowers and inclusion of asset recovery also within the ambit of this act (Jayasinghe 2023).

Marking another elite competition between the political elite and the public officials, the new act gives the three-member commission that governs CIABOC more powers over key officials in the bribery commission by removing internal checks and balances, such as hiring and firing of officials, which were previously under the ambit of another independent commission. As has been often seen, the incumbent government has always had considerable power to appoint members they prefer to the commission, navigating constitutional barricades. This means that increased powers often become subverted for political control and consolidation. Effectively, the role of bureaucrats (judiciary and public servants), an otherwise key elite group in checking arbitrary political power, becomes weakened and/or neutralised. The new bribery law illustrates how a reform increases efficiency and effectiveness of institutions to deal with an issue, while drastically buttressing the powers of incumbent governments to subvert the legal machinery to safeguard themselves and weaponise it against political opponents.

4. Anti-Terrorism Act

A draft of a new Anti-Terrorism Act (ATA) was gazetted by the government in March 2023, with the aim of replacing the Prevention of Terrorism Act (PTA) of 1979. Following widespread pushback, the presentation of the bill in parliament was postponed. A revised act introduced in September 2023 retains problematic aspects, such as the broad definition of terrorism, authorising prolonged detention without charge, and granting excessive powers to the executive (CPA 2023).

There is broad consensus among the major political and social groups that the PTA, a draconian law which emerged at the onset of the civil war, is outdated. The ATA is the government’s bid to reform the PTA, which has in the past, impeded the country’s access to trade privileges such as the EU’s GSP+ scheme. The proposed bill is a mixed bag, introducing transparency of prisons and detention centres and bringing the bar low on the repression side. However, its extremely broad definition of terrorism and lowered bar for arresting people under the suspicion of terrorism empowers more state actors with arbitrary powers than even the existing PTA does.

When mapping the discourse around the ATA, the President and cabinet, i.e., the ruling political elite, have the most to gain from it. The security sector is the other group of elites empowered through iron-fisted acts of this nature. These actors are pursuing a zero-sum game to ensure they retain power, weaponising the bill to be mobilised against groups demanding ‘system change: sections of protestors, trade unions, media, and civil society. It also appears that some powerful international elite groups such as the IMF that demand better economic governance seem unlikely to hold the government to stringent democratic standards as long as their economic targets are met. However, geopolitical actors including Western embassies, where diaspora communities reside, have raised concerns about laws that threaten such democratic aspects of governance.

Opposition political parties, such as the SJB, TNA, and NPP, were also united in their rejection of the act. This is likely driven by fears of what such reforms might do to their own freedoms to operate as non-incumbent political actors. Minority political parties such as the TNA and ACTC have been especially active in mobilising campaigns to repeal the PTA in the past, due to the disproportionate negative impact of the act on the minority Tamil community. Strong opposition to the ATA emerged from several civil society groups. Their main concern was that the new act provided even more powers to the executive and security forces to restrict freedom of expression and dissent, in the guise of national security. The way in which the civil society, which has a liberal inclination, responds with regard to reforms reflects what they (probably unconsciously) perceive a cleavage in the government of UNP and SLPP. Key civil society groups generally support liberal economic reforms that the President seems to spearhead and take opposition to reforms that securitises the state, which are associated with the SLPP faction of the government.

Conclusion

Mapping elite groups and interests in the context of reforms is a useful exercise to understand better why some reforms face more resistance than others, how they are likely to be shaped, and impact upon the people and institutions. In studying the politics that surround various reforms, a few trends are observed.

First, while implementing reforms mandated by the IMF’s Extended Fund Facility arrangement, reforms are prioritised selectively. For instance, the implemented income tax reforms aim to raise government income by 100 billion rupees. In contrast, the state airlines’ losses are over 160 billion rupees but is more or less absent as a reform item in the official reforms discourse or timeline. This is an illustration of how ruling elites try to safeguard their interests and pass on the burden to the lower rungs of the society, following its remarkable recovery from the severe setback in 2022. In doing so, they have quickly appropriated and diluted ideas generated from among the protests last year such as setting up mechanisms of participatory democracy. In consolidating their power, the ruling elite try to bypass the multi-elite power compromise among government, the opposition, and civil society in the form of the Constitutional Council, by keeping to itself the hiring and firing powers of members to new commissions they propose to set up, such as recently for online safety and electronic media regulations.

When proposing reforms, ruling elites also use tactics such as sequencing them in a particular order to overload those affected, who must now deal with several reforms simultaneously. Another apparent tactic is decoying laws with other purported reforms, so as to misdirect attention while the ‘principal’ reform passes with limited resistance. The proposed laws also allow for very limited public consultation and provide a short time window to engage them. The only time the ruling elite would commit to broad consultations is when there appears to be a critical mass of support to pass these laws initially.

The dynamics discussed in this article also reconfirm the thesis that where IMF reforms happen, they generally try to serve both local and global elite interests. These interests are sometimes complementary and sometimes contradict one another. It is in this intersection that the reforms take on a distinct national trajectory and where domestic pushback on the reforms process is enabled.

On reforms concerning fundamental rights, the governing elite follows a tick-box approach, complying with some procedural elements of democratic governance and transparency (mainly to qualify for Western economic benefits), while undermining the essence of equality and democracy. These reforms, when they are proposed and if passed as they are without resistance, will have the effect of flattening out other elite groups. This allows a core political elite to emerge as a nodal super-elite and establish themselves as paramount and indispensable.

References

Athukorala, Prema-chandra (2023): “Sri Lanka’s debt restructuring challenge,” 19 August, East Asia Forum, https://www.eastasiaforum.org/2023/08/19/sri-lankas-debt-restructuring-challenge/.

CPA (2023): “Proposed Anti-Terrorism Act (ATA) – Preliminary Comments,” 19 September, Centre for Policy Alternatives, https://www.cpalanka.org/proposed-anti-terrorism-act-ata-preliminary-comments-september-2023/.

Counterpoint (2023): “Governor Central Bank makes a presentation to the Cabinet on domestic debt optimization,” 28 June, https://counterpoint.lk/governor-central-bank-makes-presentation-cabinet-domestic-debt-optimization-2/.

Dias, Sunimalee (2023): “TUs oppose new labour law reforms,” 23 August, The Sunday Times, https://www.sundaytimes.lk/230827/business-times/tus-oppose-new-labour-law-reforms-530427.html.

Do Rosario, Jorgelina and Rodrigo Campos (2023): “Exclusive: Sri Lanka’s bondholders send debt rework proposal to government, sources say,” 16 April, https://www.reuters.com/markets/asia/sri-lankas-bondholders-sent-debt-rework-proposal-government-sources-2023-04-14/.

EconomyNext (2023): “Sri Lanka’s new anti-corruption law ignores asset recovery, retroactive action: SJB,” 22 June, https://economynext.com/sri-lankas-new-anti-corruption-law-ignores-asset-recovery-retroactive-action-sjb-124186/.

IMF (2023): “Transcript on IMF-supported EFF program Press Briefing for Sri Lanka,” 21 March, International Monetary Fund, https://www.imf.org/en/News/Articles/2023/03/21/tr032123-transcript-of-sri-lanka-press-briefing.

Jayasinghe, Uditha (2023): “Sri Lanka parliament passes anti-corruption bill without vote,” 12 July, Reuters, https://www.reuters.com/world/asia-pacific/sri-lanka-parliament-passes-anti-corruption-bill-without-vote-speaker-2023-07-19/.

Ministry of Labour and Foreign Employment (2023): “Call for Inputs on Labour Law Reforms in Sri Lanka,” https://labourmin.gov.lk/wp-content/uploads/2023/05/ENGLISH-1.pdf.

NewsFirst (2020): “Forensic Audit on CBSL Bond Scam reveals huge losses,” 23 Jan, https://www.newsfirst.lk/2020/01/23/forensic-audit-on-cbsl-bond-scam-reveals-huge-losses/.

North, Douglass, John Joseph Wallis, and Barry R. Weingast (2009): Violence and Social Orders (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press).

Nye, Joseph V. C. (2011): “Why Do Elites Permit Reform?” The Annual Proceedings of the Wealth and Well-Being of Nations, p. 53, in Emily Chamlee-Wright, ed., Beloit College, 2009, https://ssrn.com/abstract=1940192 or http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.1940192.

Ondaatje, Anusha (2023): “Sri Lanka inflation eases further in July providing reprieve,” Bloomberg, July 31, https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2023-07-31/sri-lanka-inflation-hits-single-digits-first-time-in-20-months#xj4y7vzkg.

Presidential Secretariat (2023): “Let’s collectively advance the 13th Amendment to the Constitution for the future betterment of the nation,” https://www.presidentsoffice.gov.lk/index.php/2023/08/09/lets-collectively-advance-the-13th-amendment-to-the-constitution-for-the-future-betterment-of-the-nation/.

Reuters (2023): “The countries in the grip of debt crises,” 25 February, https://www.reuters.com/world/countries-grip-debt-crises-2023-02-24/.

The Island (2023): “Banks welcome CBSL Governor’s assurances on DDR,” 30 June, https://island.lk/banks-welcome-cbsl-governors-assurances-on-ddr/.

The Morning (2023): “Sumanthiran’s PC Election (Amendment) Bill gazetted,” 11 May, https://www.themorning.lk/articles/B1TWbhTiS4Vobeh5clyR.

Harindra B Dassanayake and Rajni Gamage

This article was originally published in Economic and Political Weekly on 09 December 2023.

Image Copyright (c) 2023 Nazly Ahmed and made available under an Attribution-Noncommercial-Share Alike 2.0 license

To download the article, please click the link below.