The first phase of the relief drive was conducted in Waikkal, Thoppuwa and Pelampitiya in the Puttalam and Kegalle Districts in December 2025 and January 2026 using the funds raised from a fundraiser for the families impacted by Cyclone Ditwah. Out of the total sum raised, AUD 5,530 (equivalent to LKR 1,134,232.22), a total of LKR 417,675.82 has been spent (please click the hyperlink which has a publicly viewable spreadsheet account of all goods purchased).

The donation drive aimed to distribute food ration packs to the affected communities. Upon speaking to the affected communities on an individual basis, it was surmised that while food rations were necessary in one location, the other two locations were requesting for more household items, as they had received sufficient food rations by then. Moreover, some of the initial locations we had shortlisted informed us that their need was not as urgent, or that they were receiving sufficient aid, and to focus on more urgent areas. In landslide-affected areas, communities are still in limbo as they are staying at temporary shelters and so we paused the aid distribution, in order to meet their needs once they move back to their houses or have rented a temporary living space.

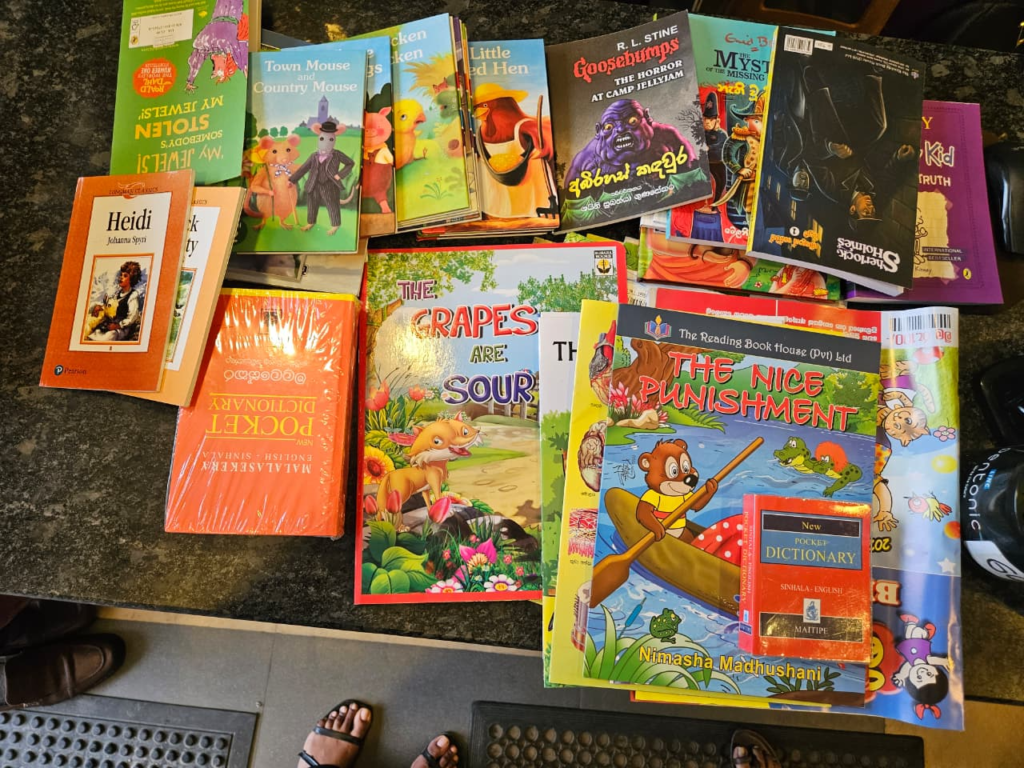

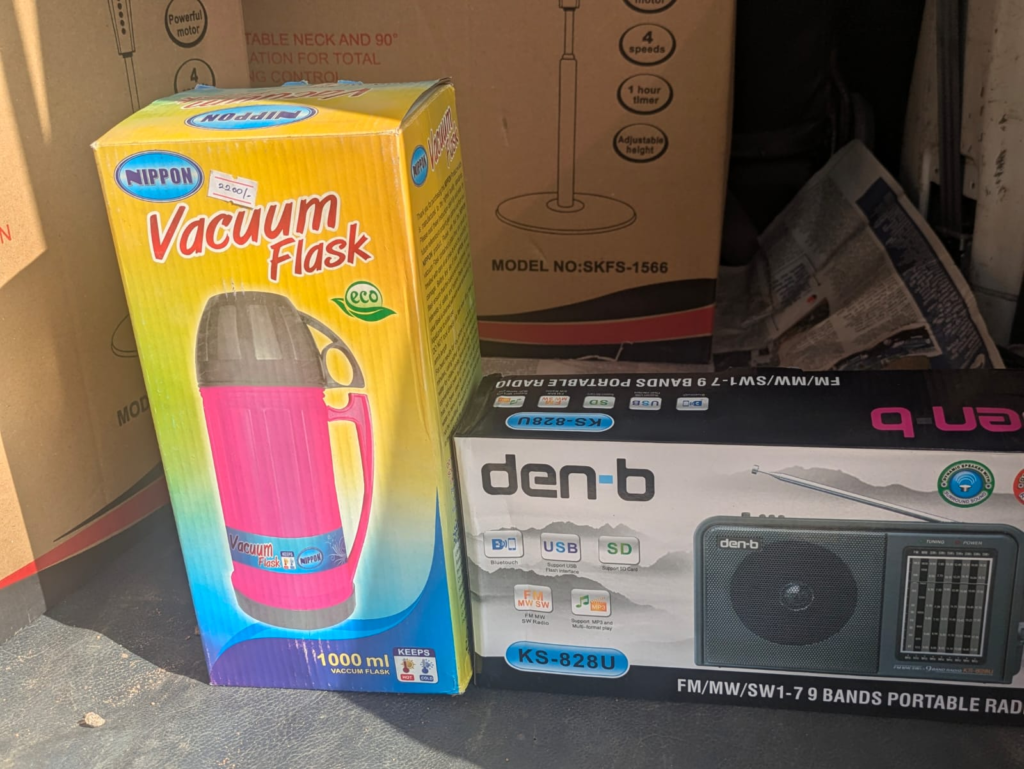

The relief items distributed included 43 books for children; 20 packets of 400 g salt; 50 litres of coconut oil; 50 packets of 100 g pepper powder; 20 packets of 50 g cinnamon; 30 packets of 100 g mustard seeds; 30 packets of 100 g fenugreek; 10.025 kg of garlic; 5.032 kg of white peas; 5.016 kg of green gram; 5.014 kg of chickpeas; 60 packets of 100 g chilli flakes; 5.1 kg of karawala (dry fish); vegetables (5+ kg each of kekiri, cooking mango and pumpkin); 100 eggs; and 20 coconuts. Non-food items included mattresses – double bed (6×4) ×4 and (6×6) ×2; gas cookers ×4; rice cooker ×1; industrial gas stove ×1; fans ×2; kitchen utensils (clay pots and spoons) ×31; clothes vouchers ×10; shoes and slippers vouchers ×10 ×2; sarongs ×4; a small radio and TV (donated separately by an individual) ×1; thermal flask ×1; and food ration packet (Nestamalt, biscuits, etc) ×1, and 120+ cloth items, children’s toys, and some stationery items.

In the second phase of the relief which will be conducted in February 2026, we will be reaching out to communities in Kotmale, Gampola, Matale and Kandy.

The following is an account of the relief drives and of the needs of the communities articulated by them. Photos of any private spaces were taken with permission.

Relief Drive One: Thoppuwa and Waikkal, Puttalam District

Muragala: CPPP’s first relief drive took place in two flood-affected riverside communities in Thoppuwa and Waikkal. On December 18, we visited 10 of the affected families in the areas, to meet and get a sense of what their urgent and evolving needs are. On December 28, we carried out the donation drive. While this method is slower, we thought it was important to spend time talking with the families, so that their needs, as articulated by them, can be mapped.

In these locations, locals spoke of how the scale of destruction far exceeded what residents had previously experienced during past major floods. Almost every household spoke of floods before, but emphasised that this time the water levels were unprecedented, rising higher, moving in with a dangerous pressure and descending faster. Mud lines on walls, fallen structures, and garbage and debris strung on high fences bore witness to how deeply the floodwaters had entered both homes and lives.

In Thoppuwa, the first family we visited lived at the very edge of the river. One entire side of their land had collapsed into the water, including their toilet, and what used to be the margin of their land was now marked only by the top of a coconut tree. The family attributed the damage to a recently constructed bridge, where promised riverbank protection had never materialised. With no stone barrier, floodwaters had swirled and eroded the soil beneath their home, causing the latrine section to fall away completely. The mother spoke of officials suggesting relocation. She asked how does one leave land where generations of family history are rooted? For now, they were struggling with basic dignity, building a temporary toilet while relying on neighbours, uncertain how long such arrangements could last, whether they would have to leave and where to, and how such an enormous task was possible.

Family number two and three, which were next to each other, were part of a larger housing cluster (these houses were yet again at the edge of the river and therefore most of their land had been washed away into the river). A few houses there had been completely flattened to the ground where some were left behind only with their structures and the others had become rubble. As the entire land area looked like it had been tossed and turned-disrupting the structure of the setting, to ensure that the underground water pipes were not further damaged, they had placed large iron table frames to keep it together. The gentleman from family number three-albeit being devastated by the damage incurred-was resolute about not relocating to any other place. His reasoning was that most of them were informal workers who had familiarised themselves with gigs in and around Thoppuwa, Waikkal and the vicinities.

Nearby, less than 500 m away, a 55-year-old man recounted how he survived by climbing onto an old railway bridge as the waters rose around him. Entire houses nearby had been flattened. His home still bore political stickers and a framed photograph of Vijay Kumaratunga, which he was carefully cleaning after it had been submerged. There was a strong emotional attachment to both land and memory here that made the idea of relocation almost inconceivable. The area was apparently used for communal food gatherings. In the house adjacent to this, which had also been completely submerged by the floods, a woman of the household showed the interior, where what used to be a living room was now empty, as most of the furniture had been washed out with the flood tide and the living room had also sunk a little. She shared that her son’s laptop which had been needed for schoolwork had been lost to the floods, as they left without preparing for the floodwaters to rise so high and so fast.

The next household was drying soaked mattresses in the open, hoping for a break in the rain. Their requests were mainly for their daughter who was in the seventh grade. All the families spoke of how their children wore casual clothes to school as their uniforms had been washed away.

In the household that was visited after this was a disabled woman, who would use a wheelchair when outside the house, but would otherwise sit on the floor at the front door of the house, watching the activity from her doorway. Her elder sister, who lives nearby and is her main caregiver, explained how the small house had been built after their father’s death. Neighbours shared how, during the flood, they prioritised her safety first and of the animals, as many in the area were raising poultry and livestock. This individual’s main pastime was to look at the TV and listen to the radio during the day, and when asked multiple times, from her and her sister, as to what was the most urgent need, they gave the same answer: a TV and a radio (they said even a second-hand one would work). They said more than food or other household items, this was what gave her the most mental respite.

The sixth household was occupied by a gentleman who did catering (from his house, or visiting a location and cooking) for a living. As we stepped into the house, we were greeted by him as well as the aroma of fried onions, chilli paste and ambul thiyal. Even though he had lost almost all cooking utensils and had no electricity, he had taken up an order for a loyal customer of his because he deemed his trade to be a service, one that he was very faithful to. He also repeatedly mentioned how he liked living life, beautifully and hygienically, because making food for the consumption of others was a sacred act. His main grievance was that he had built a beautiful life, inside-out, by growing flowers in pots and tending to them, but now they were all destroyed. Despite the fact that the flood had not spared anything, he was thankful that he was alive, and this meant that he could start over, and for this he wanted cooking utensils, a mattress to sleep on and a stove to cook his food on.

A few houses down the road, we met a mother and a daughter, who resided with each other. In total, 5 people lived in that house, including the mother, her husband, her daughter, her son-in-law and her grandson. They were cleaning and drying whatever it was that they could save from the mud, and this included plates, school water bottles, cups, and utensils. They too were drying mattresses but had lost hope in using them again. They said that most aid rarely made their way towards their houses and that they are in need of help. The daughter used to sell home-made carpets and the mother had chicken pens where the hens were used for eggs and the others were fighter chickens (pora kukullo) which were sold. However, both these trades were disrupted because the flood had washed away all carpet material and the chicken coops; the mother had made up her mind to discontinue her chicken trade whereas the daughter was still undecided about her carpet business. To at least begin to fill in the gaps of what they had lost, they wanted a mattress to sleep on, school shoes for their grandson, footwear and clothes.

The mother of this house then directed us to another house with a lady who had severe diabetes. She lived with her husband, her son and her grandson. Her daughter-in-law was abroad. She told us how because of her condition she had to frequently attend the clinic, and it cost them LKR 2000 per trip in a tuk tuk, just for transportation. Her husband, who used to work for a daily wage now could not go to work because he had to clean the mud and also take care of his sick wife who found it hard to walk. Therefore, the financial struggle was palpable. Additionally, because the water had weakened the walls and the scaffolding of the house, there was also a danger of walls collapsing, so leaving his wife alone was now even more dangerous. They said that 5-6 people from the Army helped them clear out most of the mud, but they still had so much cleaning left to do. A common sentiment shared across all houses was that this level of damage from a flood was unprecedented, so they are struggling to navigate the aftermath of it.

Across this house, a few feet away, was a family that was yet again cleaning utensils and discarding most of their electronics. They recounted how the water levels rose at night and they had no choice but to lock the house and leave. Because they estimated the floodwaters to only reach levels that the previous ones had reached, they stacked their important goods and objects on fairly tall cupboards so that they could rearrange them once they got back in a couple of days, the drill that they were accustomed to. But the flood waters rose up to the roof, all things had drowned and they were away from home for weeks. When we asked what they would want, they got very emotional and kept saying to give whatever we could. More than food rations, their needs appeared to be clothes, shoes, mattresses, etc.

Relief Drive Two: Pelampitiya, Kegalle District

While for Thoppuwa and Waikkal we used a local network to identify critically-hit households, here our relief drive was targeted towards a camp which was situated in the Sri Sambuddha Jayanthi Temple, Pelampitiya, where it was said that there were around 60 people displaced from the landslides that had occurred in that area.

Prior to visiting the place, we asked them what they required and it was oil, salt, dried fish, vegetables, coconuts, eggs and books for the children, as they were apparently building a small children’s library for the children in that area. They said that they had dry rations such as rice and potatoes but that they wanted more nutritious and protein-heavy rations for the community.

During the drive up to the Temple, we stopped at a place where a large landslide had happened and had fundamentally altered the landscape. 6 houses and a bungalow had been completely demolished in the process, causing 12 deaths where only 5 bodies had been recovered. Warnings had been sent to other people residing in its vicinity asking them to move out from their houses because they were in a red zone.

After we reached the temple, the Samurdhi Officer relayed to us the series of events that took place from the severe landslides, the novelty of this climate catastrophe, to the destruction of tea estates, which was the main source of income for most people, loss of livelihoods, strong attachment to the place which made being relocated a difficult but non-negotiable reality to grapple with, the mental trauma which manifested as rising blood pressure and even heart attacks. Currently, families from households that were marked off as existing in the danger zone and the ones whose houses haven’t been assessed/evaluated yet resided in the temple. She also added how the main thing that kept them going during these difficult times was the sense of community.

Villagers told us that in total nearly 50 houses were vacated, however they said that no one had received any financial compensation. They said that all they had received was aid to the camp from private donors. However, they did acknowledge that the military had been very prompt in helping build a new road in a few days, when the previous road just fell off the cliff. They also acknowledged that the state had sent them medical teams.

They said that they had been hoping that they would be given the LKR 25,000 rupees that was promised as rent money until they were redirected towards a permanent abode. They also mentioned how the landlords who used to rent their lodgings for LKR 5000-6000 were now increasing the value up to LKR 25,000 because that was the amount that the government had promised the people who were displaced. While we were driving we saw two families packing their belongings in a lorry, and vacating their houses. With rain continuing, they said they were very afraid to return to their houses, especially when there were cracks in the floor of the houses, or when one area of the house had sunk lower than another side. There were some who said they were told they would be given temporary housing elsewhere in government-built apartments, but that would be too far from their small tea estates which were the livelihood of many of the people in this village. They asked how they could leave their homes, where the air and water was so clean, and live in an apartment. They could not imagine such a future, or go back to their homes, and their lives were in limbo, even as the news cycles had moved far past Cyclone Ditwah.

Record of financial expenses

A complete breakdown of financial expenses and the receipts can be viewed at https://docs.google.com/spreadsheets/d/1AE0BmHfeHzwj3y2GQfb96wxdacyo_9QKt3IL85abwSc/edit?gid=0#gid=0. In addition to these funds, we also received over 120 secondhand clothes, and some stationery items, cooking utensils and children’s toys, which were also distributed to these families.

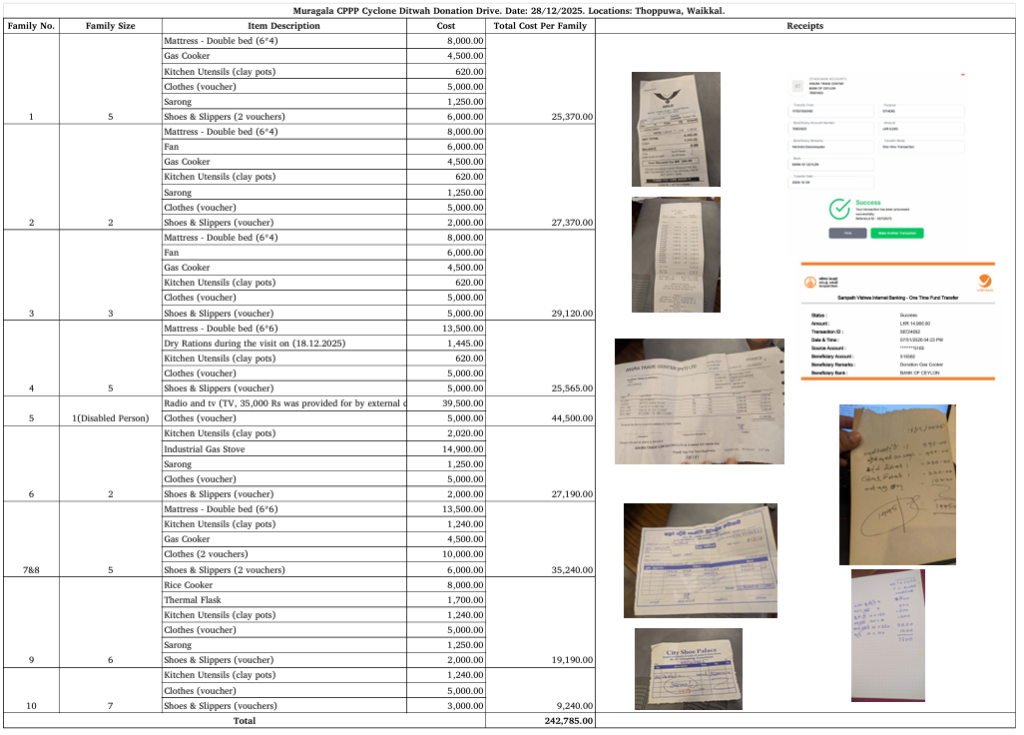

Financial accounts of Relief Drive 1:

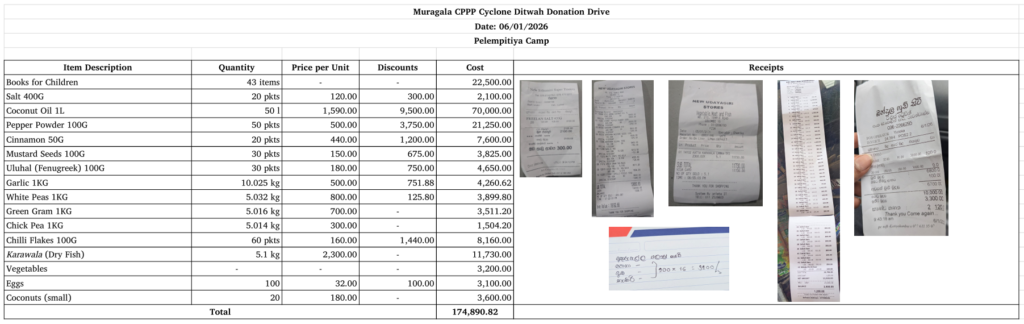

Financial accounts of Relief Drive 2:

Photos from both relief drives of the goods and other items distributed

This narrative report was compiled by Sandunlekha Ekanayake and Manuja Wijesuriya, research analysts at Muragala | CPPP.